M, 136 minutes

4 Stars

Review by © Jane Freebury

Making a film from a novel is a tricky business. Page and screen are vastly different, unless we’re talking graphic novels. With inverted commas around the title, this new take on the Emily Bronte novel published in the mid-1800s tries to pre-empt criticism of the accuracy of its adaptation. It was good to take some precautionary measures, because this is a bold, sensual and occasionally satiric response to a classic of English literary fiction.

I read it so long ago, while a student of English lit, and recall that I wasn’t particularly drawn to it. So inward looking, claustrophobic and brooding. I hadn’t liked sister Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre that much either, so I was intrigued to see what Emerald Fennell, someone whose work I really admire, was going to do with it. The director of Promising Young Woman, and Saltburn, one of the writers on Killing Eve and the actress whose Camilla made an impression in The Crown, she has built quite a reputation as an exciting new female talent, and a bracing satirist. Wuthering Heights seemed like a completely new direction for her.

a bold, sensual and sometimes satiric response to a classic of English lit

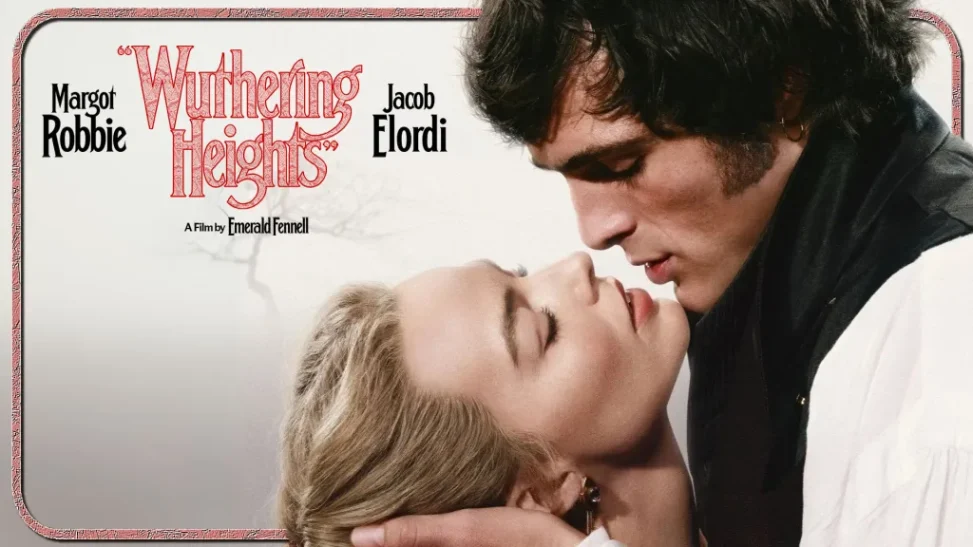

Does she tamper much with the intensity of the romance that the advertising invites us to watch and then ‘come undone’? Fennell revels in it, supported by actors Margot Robbie as Catherine Earnshaw and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff who make a thoroughly believable couple. Forever apart because of the social prohibition on a daughter of the landed gentry marrying a servant of unknown background, and forever longing for each other. The actors occasionally let slip their Yorkshire accents and betray their Aussie origins, slightly distracting when it happens, but the friendship and passion they portray is easy to believe. And that’s saying something, when wardrobe and production design departments compete for our attention too.

Clearly, writer-director Fennell wanted to focus on the family dynamics and the social system that were in the background of this enduring passion. Why two young people were drawn to each other in the first place, what they bonded over, how their friendship was transformed to passionate love, and how those who upheld the class system kept them apart is all made plausible. This includes the role of the housekeeper, Nelly (Hong Chau), who inserted herself in various meddling ways, seeing to it, in her belief that she was doing her job, that Catherine and Heathcliff would never be together.

To underscore its appeal for its target audiences, most likely young and female, the movie has a highly stylised look and a lavish score to seduce the senses. Why spend more time than necessary on bleak, windswept moorland, when there are opulent dresses and outlandish jewellery to admire? On the other hand, the fashions Catherine wears when she becomes the wife of Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif), her wealthy neighbour, are a form of entrapment, and as dazzling as they are ridiculous. Catherine has nothing else to do but be decorative.

such a thoroughly believable couple, even while wardrobe and production design compete so for our attention

Through marriage to kind Linton, Catherine had escaped her childhood home but she remains trapped, a woman without agency. Life with her brutish father, patriarch of the crumbling manor house that he could neither afford to maintain nor manage, represented a different kind of entrapment. Earnshaw, a thoroughly dissolute representative of the upper classes, is played by Martin Clunes, looking unsavoury for the role.

Handsome Heathcliff, on the other hand, the man from nowhere who was rescued by Earnshaw as a foundling in Liverpool, is a disrupter. The mysterious, exotic stranger, a classic literary device, who messes with everyone’s lives, and upends the system. He returns after five years abroad a wealthy man who can afford to buy the Heights estate – and have his teeth fixed.

It is fascinating to be reminded that Emily and Charlotte Bronte lived with their widowed father, a curate, in the same isolated corner of England where Wuthering Heights is set. They never married and they died young. No doubt, the yearning the sisters have instilled in their famous books has contributed to its enduring place in popular culture.

Fennell has even been so bold as to include some queasy scenes of domination and kinky sex. It reminded of Jane Campion; another filmmaker whose work carries a feminist critique, and at the same time a refreshing willingness to explore the nature of desire and its contradictions.

Published in the Canberra Times online (in print on 14 February 2026) and on Rotten Tomatoes